Introduction

Traditional Food is a topic extremely close to the hearts of Japanese. Japanese cuisine, or washoku, is the first thing to come to mind when talking about traditional food. This article focuses on the preservation, taste and regional aspects of some of the most predominate traditional foods in Japan.

Washoku has even been registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. We will not only look at washoku as simply a Japanese style of food but also as a renowned food culture embodying the spirit of the Japanese people (Table 1). This means we must delve into washoku from the aspects of the cooking as well as the traditions and culture.

Table 1. Elements of Washoku Culture

|

Ingredients |

The warm humid climate in the north-south island nation of Japan is perfect for a diverse range of fresh foods Eg.:Rice, traditional vegetables, (daikon or Japanese radish, spring onions, etc.), Japanese peppers, wasabi, and green tea |

|

Table Etiquette |

Nutritional balances dishes presentes with the essence of each season and use of chopsticks Eg.:Bowls, chopsticks, arrangements illustrating the four seasons, and PFC(1980) |

|

Preparation |

Washoku uses cooking techniques and utensis that will bring out the best taste of the ingredients Eg.:Soy sauce (fermented food), sashimi, knife work, dashi, and umami |

|

Japanese Traditions |

Traditional events that wish for health and longevity and traditions intimately rekated to and customs of famillies and local communities Eg.:'Itadakimasu' or expression of gratitude said before meals, yearly festivals, and local harvest festivals |

Foundation of Traditional Japanese Cuisine

The Japanese Society of Traditional Foods deems washoku a tradition passed down over time by a people rather than a certain type of cooking.

I believe the techniques to preserve the food as well as the skill to bring out the best flavor are key to the reasons why washoku has been passed down one generation to the next.

The food processing technology we find in modern times from freezing and refrigeration to vacuum packaging has come a long way. The well-established transportation and distribution networks deliver foods to manufacturers and consumers in no time. This allows homes throughout Japan to have foods on the same table from the most northern region of Hokkaido to the southernmost tip of Okinawa.

An era before developed technologies and infrastructure was not quite the same. Individuals and families were responsible for their own foods, and there were very few means to obtain foods. Some days, people were not even able to find foods. Moreover, in more severe climates, finding foods became even more difficult. People needed the ingenuity to preserve older food somehow for days when fresh foods were not available. This required effective ways to store food. All of these considerations were something thought natural in daily life.

As a result, people then had to strive to better the taste because some techniques to preserve foods for a certain period of time left food flavorless. Even in modern times, some popular products disappear while others find a foothold after some time passes. Our ancestors were excellent at heightening preservation and preparation methods, which always seemed to enhance taste. The pursuit of both rich flavors as well as a longer shelf life are indispensable in the traditional foods passed down to the next generation.

Regional Nature of Traditional Food of Japan

Kyodo Ryori, or local cuisine in Japanese, celebrates the roots of the unique washoku passed down in each local region.

Many researchers have an abundance of hypotheses about traditional food and local cuisine with many different terms to illustrate these phenomena. However, I agree with Okamoto and her team that traditional food is the food made from locally produced ingredients eaten by people of the community since long ago while local cuisine is food made from unique local ingredients in a way suited to that region. In other words, traditional food refers to ‘ingredients’ while local cuisine refers to ‘dishes’. Local cuisine also includes dishes that use traditional food as well as new dishes conceived of as part of tourist ventures through activities to cultivate local production and consumption and movements to revitalize local communities.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Japan Tourism Agency as well as the Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO) established JAPAN’S TASTY SECRETS to widely publish articles about the renowned local cuisine of Japan. (http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/topics08_000005.html) Kusaya, Funa-zushi and other traditional cuisine is treated as local cuisine in this magazine, but local cuisine also has dishes that use Hoba Miso, Kiritanpo-nabe and other traditional food as ingredients.

Ingenuities of Preserving Traditional Food

Having no contamination by hazardous microorganism is an absolute must in preserving food. Today, raw foods bought at a grocery store can be stored for long periods of time thanks to refrigerators and freezers. However, in an era before refrigeration, the ability to save food in a way that it would not rot was a major concern.

People long ago put much time and effort into cultivating and incorporating the knowledge necessary to store food. These techniques emphasized drying, smoking, curing, pickling and fermentation. The methods employed demonstrate the foundation of many traditional Japanese foods.

Drying, smoking and curing better preserved food by reducing the amount of moisture to limit the spread of harmful microorganisms. Pickling food boosts the longevity as well by reducing pH levels, which also limits the spread of harmful microorganisms. Preservation through fermentation purposely breeds microorganisms to help better preserve food. Even in modern food processing, all of these techniques are incorporated to prevent food from spoiling. Those who came before us forged innovative ingenuities in daily life to give modern society traditional food which combines these techniques.

Let’s take a look at the difference between fermentation and rotting while we are on the subject. Fujii distinguishes fermentation as a technique beneficial to people’s lifestyles through microorganisms while rotting is caused by the harmful act of microorganisms. The distinction between whether beneficial or harmful is based on personal beliefs and not a difference in the actual microorganisms.

Everyone would be surprised to hear the fermented traditional foods that Japanese eat on a daily basis uses mold in fermenting.

Mold, such as Aspergillus Oryzae, is a very well-known microorganism used when brewing Japanese sake.

In 2006, The Brewing Society of Japan recognized Aspergillus Oryzae as a national microorganism. Aspergillus Oryzae, or koji mold, stands next to the rising sun as the Japanese flag, the cherry blossoms as the national flower, and the green pheasant as the national bird.

Koji mold is not only used in brewing sake but also many familiar products used in preparing traditional Japanese food from soy sauce and miso paste to pickled vegetables and vinegar.

Refined Flavors of Washoku

I have introduced some of the techniques used by our predecessors to preserve food. In addition to the ingenuities that enhanced the preservation of food, we must not forget the skill required to better the taste.

The technique to dry food in the sun does not ruin the true richness of each ingredient that is either left untreated, cured or boiled to heighten the flavor by concentrating the flavors. Drying food such as sea cucumber not only enriches the flavor profile but also offers a texture distinctly different from fresh meat.

Smoking food in ways unique to each ingredient provides greater aromatics such as polyphenol compounds and aldehydes brought forth from wood such as broad-leaved trees, which is not fully combusted. The process eliminates unwelcome smells such as the gaminess of fish or meat to offer a taste perfect for our palate. Smoking food had once been done only to preserve food for storage, but many foods like smoke salmon are sought after today for their delicious flavor.

Curing penetrates food with salt for a salty flavor which makes food even more tasty. Salted fish guts, fish sauce and other similar foods pack a variety of flavors with a greater number of peptides and amino acids through enzymes found in the fish while the curing prevents any contamination of microorganisms.

Fermentation is an extremely unique technique that preserves food and adds flavor through microorganisms. Many traditional Japanese foods stem from fermentation that vastly differ in the foods and microorganisms that are used.

Natto, for example, is a traditional food made from soy beans fermented with natto bacteria, which is a specialty of Ibaraki Prefecture. The process creates an unmistakable flavor and texture achieved through numerous flavor components from amino acids, peptide and polyglutamic acid that make the natto sticky. Another example is the Goishicha from Kochi Prefecture by fermentation of tea leaves included mold(Aspergillus species) and lactic acid bacteria.

The microorganisms reduce the catechin, which is one component that makes tea bitter, while increasing the lactic acid for a wonderful mild bitterness in tea that is much more sour than other teas. Sunki-zuke has been made for generations in Nagano Prefecture by fermentation of turnip leaves with lactic acid bacteria. Sunki-zuke does not use salt in the pickling process and people enjoy the freshness and moderate sourness produced by the lactic acid bacteria that transforms the sugar group of the leaves into organic acid.

Now, I would like to focus on two of the most well-known washoku delights illustrated on the cover miso and dried bonito. Both miso and dried bonito become more flavorful with a longer shelf life thanks to Aspergillus Oryzae or the drying nature of Aspergillus species, which is a similar mold to the national microorganism.

Miso

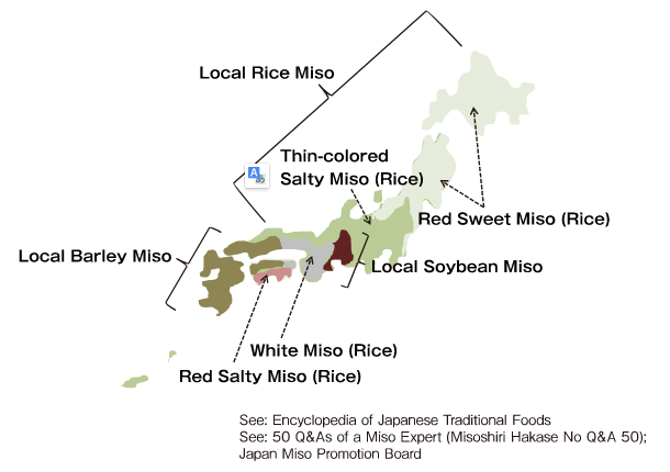

There are many different types of miso with unique foods and production methods throughout Japan. The amazing preservative properties and high nutritional benefits made miso perfect for a military ration during the war. The various types of miso are said to come from the agriculture and climate found in each region. This means miso is a traditional food deeply rooted in the region where it is made(Figure 1).

The primary ingredient for miso is either rice, barley or soy. These types of miso are generally made with koji (rice, barley, or soybean koji depending on the grain) to spread koji mold. There are many different kinds of rice and barley miso with unique flavors and colors. Rice miso makes up 80% of the total miso produced in Japan. Moreover, Kyushu is well-known for barley miso while the Tokai area is renowned for soy bean miso.

Figure 1. Various Miso and Regions

Miso starts with a fermented bean paste made from koji mold in a starch of rice, barley, or soy. Koji, steamed soybeans, and salt are added all at once to a preparation tank to start the fermenting and maturing process. This transforms the raw ingredients at a lower-molecular level while they ferment and mature to produce a delicious miso flavor as the microorganisms tolerate the salt content.

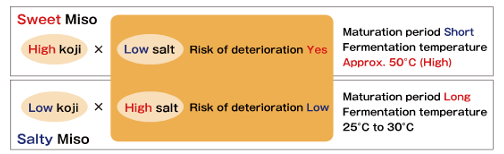

Grocery stores offer a choice of sweet (amakuchi) and salty (karakuchi) misos. The blend of koji and salt determines whether a miso will be sweet or salty. The decided rule of thumb for the blend of koji and salt is to adjust the period for maturation and temperature for fermentation by considering the preservation through the amount of salt (Figure 2). As a result, the effect produced by the fermentation and maturation inside the preparation tank varies to offer either a sweeter or saltier miso. The standard component values and alcohol content of major types of miso are indicated in Table 2.

Figure 2. Craftsmanship of Koji-Salt Blends

Table 2. Standard Component Values and Alcohol Content of Miso

|

NaCl |

DRS |

FN/TN |

Gu |

Acidity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rice Miso |

Sweet Miso |

5.8 | 25.6 | 16.6 | 273 | 6.13 |

|

Thin-colored Salty Miso (Strained) |

11.9 | 15.7 | 21.0 | 430 | 9.22 | |

|

Red Salty Miso (Strained) |

11.9 | 15.0 | 22.6 | 449 | 11.9 | |

|

Thin-colored Barley Miso |

10.5 | 17.7 | 24.0 | 486 | 9.5 | |

|

Red Barley Miso |

11.0 | 18.1 | 24.5 | 472 | 11.2 | |

|

Soybeen Miso |

11.1 | 5.9 | 29.1 | 1081 | 25.87 | |

|

ethanol |

2-propanol |

propanol |

isobutanol |

butanol |

isoamyl |

amyl |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rice Miso |

Thin-colored Sweet Miso |

T~6.1 | 2~100 | 2~32 | 6~756 | |||

|

Thin-colored Salty Miso (Strained) |

T~108 | T~136 | 15~45 | T~16 | 99~484 | T~16 | ||

|

Red Salty Miso (Strained) |

366 | 0.8~1.2 | 41~120 | 25~199 | 132~716 | 12~26 | ||

|

Thin-colored Barley Miso |

98~ | T | T~62 | 37 | T~12 | 85~323 | T | |

|

Red Barley Miso |

0.9~65 | 9~108 | 4~5 | 61~238 | 67~121 | |||

|

Soybeen Miso |

79~238 | T | T~39 | 4~346 | T~34 | 8~24 | 22 | |

Sweet miso is made at a high fermentation temperature with a shorter period of maturation. The production of organic acids and aromatics is minimal due to the limited function of the lactic acid bacteria and yeast (Table 2).

Rice, barley and soy each provide their own unique features as a raw ingredient. For example, barley and soy tend to extract more umami due to the high amount of protein while rice and barley are known to have complex aromatics caused by microorganisms transforming the sugar (Table 2).

In this way, the raw ingredients available in different regions change the flavor of the miso as a traditional food discovered from the pursuit of better preservation and taste thanks to the ingenious use of curing and fermentation techniques.

Dried Bonito

Dried bonito, or katsuobushi, is indispensable to washoku as a traditional food rich with inosinic acid.

The different types of dried bonito can be largely broken down by its production method into arabushi and karebushi (honkarebushi), which each offer unique dashi. The process and pictures for making dried bonito can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Process and Pictures of Dried Bonito

Arabushi is shavings from a well-boiled skipjack that has been smoked dried. Karebushi (honkarebushi) is Arabushi that has been fermented dry through multiple applications of koji mold which prefer a dry condition (Aspergillus species). Arabushi ordinarily creates a potent dashi from the strong smoke-dried fragrance while karebushi (honkarebushi), has a distinct aroma that offers a brilliant dashi brought about from a very mild fishiness and low fat content. Dried bonito is also a traditional food produced from the pursuit of better preservation and taste through fermentation.

The origins of katsuobushi is still being debated. Katsuobushi may have begun by drying skipjack in the sun in the Muromachi period (1336–1573) until smoke-drying techniques were actively introduced in Kumano by Kishu katsuobushi producers at the beginning of the Edo period (1603–1868).

Thereafter, the methods to make dried bonito in Kumano were incorporated in Tosa (tosabushi) and Satsuma (satsumabushi) and the area then drove katsuobushi production. The dried bonito at the time often produce adverse mold in addition to the Aspergillus species used for drying, which resulted in poor quality katsuobushi.

These craftsmen took advantage of their experience in Tosa to limit the spread of adverse mold by thoroughly smoking and using Aspergillus species to dry the skipjack, which give birth to karebushi. The desire for this new and improved dried bonito grew from these regions to as far as Edo and Osaka.

At the end of the Edo period, these Kishu katsuobushi producers spread their new and improved techniques for producing katsuobushi to Izu (izubushi) and Yaizu (yaizubushi). Izu revolutionized the decadence even further with multiple applications of Aspergillus species to dry the bonito in Yaizu. Honkarebushi is said to have come into fruition through three to six applications of the Aspergillus species.

Conclusion

The wisdom and ingenuity of our predecessors who nurtured washoku and a wide range of sensible techniques are captivating even from a scientific standpoint. In recent years, a fear seems to be growing that the techniques tied to washoku may be lost in the aging society who possesses these skills. These traditional Japanese foods may also lose their true nature with greater industrialization and changes to production methods. The time to take a moment to indulge your curiosity about washoku food and culture is now.

Daisuke Kato (2017)